The image goes viral, or as viral as it gets in the summer of 2007. We see the body of a gigantic silver-back mountain gorilla hoisted high on crisscrossing branches and carried by at least 14 men through the bush. The dead gorilla is tied with vines to secure its arms and legs. Its prodigious belly is also surrounded by vines and its mouth is stuffed with leaves. The photograph seems to be the end of a film whose beginning we do not yet know. It weighs 500 pounds – a black and silver planet in the middle of the green. Although we can’t see this part, some of the men are crying.

The gorilla’s name is Senkwekwe, and he is well known to porters, many of whom are park rangers who call him “brother”. He is the dominant male of a family called the Kabirizis. (The American primatologist Dian Fossey was instrumental in the study of the complex dynamics of these family units.) They are a troop accustomed to humans: gentle, curious, cheerful and often happy to welcome visitors, tourists. and the rangers who protect them. Now, here in their home range, on the slope of the Mikeno volcano in Virunga National Park in eastern Congo, many of them have been murdered by armed militiamen trying to scare the rangers away and take control. from old-growth forest to charcoal. manufacturing. In a solemn procession, the dead gorillas are taken to the rangers field station.

The photograph, taken by Brent Stirton for Newsweek, appears in newspapers and magazines around the world, alerting others to the issues park wardens know so well: the need to protect gorilla habitat, the bloody battle for resources (gold, petroleum, charcoal, tin and poached animals), the destabilizing presence of armed rebel groups as well as the Congolese army within the borders of the park. Although the park is a World Heritage Site, more than 175 park rangers have been killed here over the past 25 years. What is also not visible in this photo is that only one gorilla survives the massacre, a baby found next to its slain mother, one of Senkwekwe’s companions, trying to suckle her breast.

The baby – a 2-month-old, five-pound, adorable female – is dehydrated and near death herself, so a young ranger named Andre Bauma instinctively places her against her bare chest for warmth and comfort and dabs her gums and his tongue with milk. He brings her back to life, sleeps, feeds and plays with her around the clock – for days, then months, then years – until the young gorilla seems convinced that he, Andre Bauma, is his. mother.

André Bauma also seems convinced.

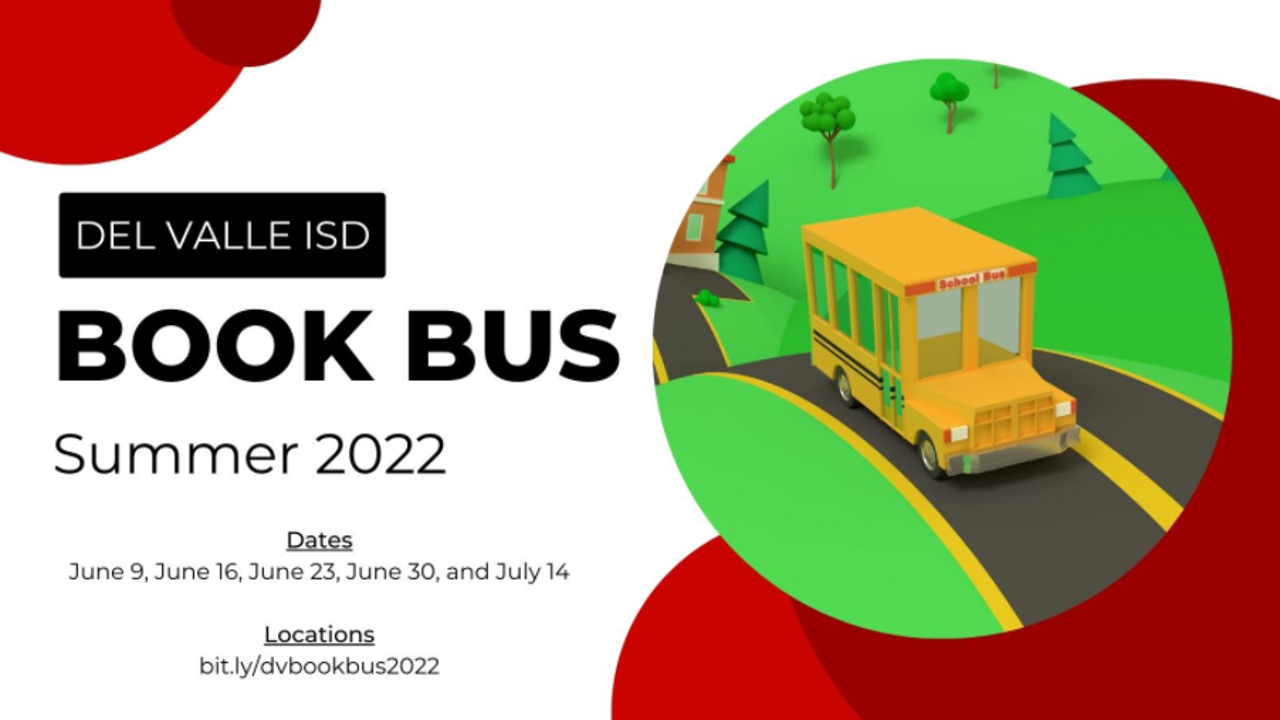

Senkwekwe, Ndakasi’s father, after being found dead in 2007.

Brent Stirton

The baby gorilla, begotten of murdered parents, is called Ndakasi (en-DA-ka-see). Because no orphan mountain gorilla has ever been successfully returned to the wild before, she spends her days in a park sanctuary with a group of other orphan gorillas and their keepers, swinging from the tall branches, munching on wild celery, even learning to finger paint, mostly oblivious to the fact that she lives in one of the most contested places on the planet. She is exuberant and a ham and demands to be carried by her mother, Andre Bauma, even as she grows to 140 pounds and he almost gives way under her weight.

One day in April 2019, another ranger takes a selfie with Ndakasi and her best friend, Ndeze, both standing in the background, one with a protruding stomach and both with whassup expressions. The cheeky blunder on humans is almost too perfect, and the image is posted to Facebook with the caption “Another day at the office. …”

The photo explodes immediately, because we love that stuff – us and them together in one picture. The idea of mountain gorillas imitating us for the camera skips borders and species. We are more alike than different, and it appeals to our imaginations: ourselves existing with a fascinating, perhaps more innocent, version of ourselves.

Mountain gorillas exhibit dozens of vocalizations, and Bauma always vocalizes with Ndakasi singing and growling and the growling belching that signals contentment and security. Whenever there are gunshots near the shrine, Bauma makes sounds to calm Ndakasi. He himself lost his father in the Congo War. Now he tells her it’s just another day in their simple Eden.

“You have to justify why you are on this earth,” Bauma says in a documentary. “The gorillas are the reason why I am here.”

A park warden taking a selfie with Ndakasi and a friend in 2019.

Mathieu Shamavu / Virunga National Park

Ndakasi turns 14 in 2021 and spends his days healing Ndeze, clinging to Bauma, vocalizing with him. Mountain gorillas can live up to 40 years, but one spring day she gets sick. She loses weight, then some of her hair. It is a mysterious disease which increases and decreases, for six months. Vets from an organization called Gorilla Doctors arrive and, during repeated visits, administer a series of medical interventions that appear to make small improvements. Just when it looks like she is going to recover, however, Ndakasi takes a bad turn.

Now his gaze only reaches right in front of her. The wonder and playfulness seem to have faded, her concentration having turned inward. Brent Stirton, who has returned to the Virunga about every 18 months since photographing the massacre of the Ndakasi family, is visiting and taking pictures judiciously. The doctors help Ndakasi to sit down at the table where they are treating her. She vomits into a bucket, is anesthetized. Bauma stays with her all the time; finally, she is taken to her enclosure and lies down on a green sheet. Bauma is lying on the bare floor next to her.

At one point, Bauma leans against the wall, then she crawls onto her knees, with the energy she has left, rests her head on his chest and sinks into him, placing her foot on his foot. “I think that’s when I could almost see the light leaving his eyes,” Stirton said. “It was a private moment no different from being with a dying child. I made five frames with respect and walked out.

One of the latest photographs goes viral, spreading the sad news of Ndakasi’s death to the world. What do we see when we look? Pain. Trial. Death. And we also see great love. Our capacity to receive and to give. It is a fleeting moment of transcendence, a gorilla in its mother’s arms, two creatures united to make one. It’s deeply humbling, which the natural world bestows, if we allow it.

Bauma’s colleagues draw a tight circle around him in order to prevent him from having to talk about Ndakasi’s passing, though he issues a statement praising his “gentle nature and intelligence,” adding: “I loved him. like a child”. Then he goes back to work. Death is everywhere in Virunga and there are more orphan gorillas to care for. Or maybe it’s the other way around.

Michael Paterniti is a contributing writer for the magazine.

Zoo Book Sales

Zoo Book Sales