My mind has been busy with Thomas Merton a lot lately. I wrote a book about his life, Thomas Merton: an introduction to his life, teachings and practices, which was released on May 18. Thomas merton was one of those “labor of love†projects that have lasted for 35 years, since I first visited Gethsemane Abbey during spring break during my second year at university. This is the Kentucky monastery where this Trappist monk – who is also, I believe, the most important English Catholic writer of the 20th century – lived from April 1941 until his accidental death in December 1968 at the age of 53 years old, which is the age that I am now.

Merton’s gist is all of these books taken together. Read them all, and in that order, if you can.

I refer to several of his books in my book. I also spoke with experts and enthusiasts at Merton about how they feel about the man and the continued relevance of his writing. And the other day I ran a poll on my Twitter feed, asking people to pick the Merton book they recommended most often. I have offered four options, which I will now share with you, along with the results.

The seven-story mountain (1948). 35 percent.

It will always be Merton’s best-known book. It is the confident account of a recent convert to the Roman Catholic faith, the story of a monk who felt he had left the world behind to find the truth. Perhaps his most famous sentence is this, as the author remembers how he felt when he arrived at the monastery: “So Brother Matthew locked the door behind me and I was locked within the four walls. of my new freedom. â€

Religious certainty may surprise readers who come to Merton first through his later works.

He had gone to the monastery thinking he would stop trying to be a poet and novelist, but his abbot then ordered him to resume writing. To everyone’s astonishment, The seven-story mountain surpassed all other non-fiction books published in 1948-49, and suddenly the monk who had wanted to live anonymously became a famous writer and celebrity.

The storytelling is powerful, and the religious certainty may surprise readers who come to Merton first through his later work.

New seeds of contemplation (first published in 1949 as Seeds of contemplation; revised 1962). 51 percent.

New seeds is a beautiful book, one of the few Christian spiritual classics of the twentieth century. It is here that Merton develops the distinction between the true self and the false self – the most essential of his teachings. Here it is, basically, in three short sentences:

1. “Each of us is clouded by an illusory person: a false self.” Consider all that we are doing, often daily, even more often than that, so as not to engage with who we are really meant to be. Simply on the physical plane – we use entertainment, food, sex, overwork, stimulants, and other things to escape our real selves.

New seeds is a beautiful book, one of the few Christian spiritual classics of the twentieth century.

2. “He is the man I want to be myself but who cannot exist, for God knows nothing about him.” (You will have to forgive these masculine pronouns in his writing.) By doing these delusional things, we think we are happy, but we are not. Most importantly, God does not know the avoiding and escaping person. God knows who we really are.

3. “To be unknown of God it’s too much privacy. “ The false self leads us to be alone without being unique, without discovering how each of us is, in some vital and real ways, unique before God.

The path of Chuang Tzu (1965). 5 percent.

It was Merton’s favorite among his own books, and it probably still shocks some readers today. Why would a Catholic monk spend so much time understanding and communicating the wisdom of a Chinese philosopher who lived three centuries BC? In the preface to the book, he mysteriously says that the right way of life in the world should never be to try to find a way out “out” of the world, but also that “Chuang Tzu would have agreed with Saint John of the Cross, that you enter this path when you leave all the paths and, in a certain sense, you get lost.

Over the last decade of Merton’s life, he was increasingly willing and able to live in the mystery of things.

So you can see how far this has evolved from what Merton wrote earlier in The seven-story mountain (and other subsequent books).

During the last decade of Merton’s life, he was becoming willing and able to live in the mystery of things, finding God in unanswered questions. The religions of the East taught him this, then he returned and found the same teachings in the Catholic spiritual tradition.

Private journals (1995-1998). 9 percent.

One gets an excellent sense of all these progressions, and more, by reading Merton’s private journals. These are journals that were not published for publication until 25 years after his death, according to the provisions of Merton’s literary field. They started to appear in the 1990s.

They follow his life in chronological order, from the pre-monastic jazz clubber in Greenwich Village to the early years at the monastery to the final year of traveling through Asia, meeting the Dalai Lama and seeking ways of deeper contemplation. The seven titles of these journal volumes say a lot about their content: Running in the mountains; Enter the silence; In search of loneliness; Turn to the world; Dance in the water of life; Learn to love; The other side of the mountain. By far the bestseller is Volume 6, in which we read the intimate details of Tom’s affair with “M”, a Louisville nurse, how they were discovered, then how and why he decided to no longer have her. see and devote his life again to his monastic vows.

The essential Merton is, in fact, all of these elements taken together. Read them all, and in that order, if you can. Meet the more confident, sometimes reactionary, convert Merton from the autobiography first. Then read his spiritual classic of monastic wisdom for people living anywhere and in any age. Follow him to the east side, where he and we can expand our understanding. Then delve into the details of his life in the newspapers, where there are so many moments of crankiness and bad judgment (he remained very human), deep understanding and quiet reflection, revealing that Thomas Merton lived a life that was extraordinary, but also ordinary. , as each of us can hope to do.

More America:

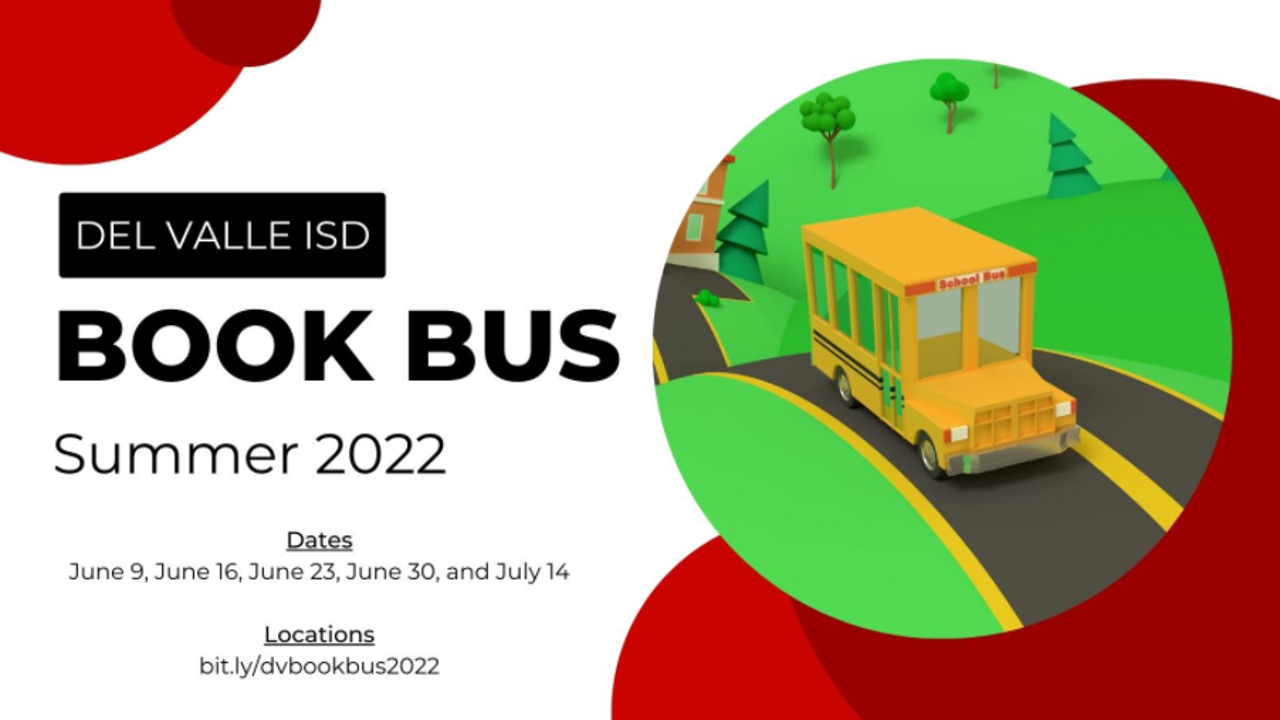

Zoo Book Sales

Zoo Book Sales